[The following was originally published as a chapter in: "Nine Feet from Tip to Tip: the California Condor through History." (Gresham, Oregon: Symbios Books, 2012).

At first glance, Alexander Taylor and Colbert Canfield seem much alike. Both identified themselves as "doctor" and "druggist." Both were early arrivals at Monterey, California. Both lived relatively short lives, even in comparison with the standards of the times. Both were regular contributors to newspapers and magazines. Both had wide ranging interests in history and natural history. Both sent natural history specimens to museums and other collectors, both in the United States and abroad. Both had a strong interest in California condors. As similar as all that seems to make them, they were clearly very different types of individuals.

Colbert Austin Canfield, son of Austin Canfield and Lodemia Benton, was born at Chardon, Geauga County, Ohio, in 1829 [1, 2]. His was a farming family, but he received a medical education at Western Reserve Academy (Hudson, Ohio) [3]. He worked for a year or so with Dr. Sherman Goodwin in Chardon [4], but in March 1853 he joined a friend, Wallace John Ford, on a trip to California via New York and Panama. In California in early 1854, he went with Ford from San Francisco to Los Angeles, to bring a herd of cattle north. He may also have worked with Ford hauling merchandise to northern California towns [5]. By 1855 he was living in Monterey County, and before long had established a medical practice there [6]. Reportedly, he was "the first resident physician at The Presidio" (although it's unlikely he was actually a part of the military staff) and also "an official at the old customs house in Monterey" (although this statement may relate to his later political positions) [7].

Dr. Canfield's first few years in Monterey appear to have been involved mostly with establishing his medical practice and starting a family. In 1858, he married Anita Watson, daughter of James Watson and Maria Anna Escamilla, and their first of five children was born 5 February 1859 [8]. The first written account I have found for him was in January 1858, when Alexander Taylor (of all people!) described a possible stage route from San Francisco to Fort Tejon, based on information he had received from Dr. Canfield [9]. Later that same year, Canfield made his first personal appearance in print, with a letter to the editor correcting the story of how many children a certain California lady (a patient of his) had borne (twenty-four, not thirty-six!) [10]. But it was a letter he wrote to Spencer F. Baird, Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, on 10 September 1858, that gives us our first look at Dr. Canfield, the naturalist.

Canfield had just read Dr. Baird's account of the pronghorn antelope in Volume VII of the "Pacific Railroad Surveys" [11]. Knowing from his own observations that some of what Baird had written was incorrect, and that he obviously knew some things about pronghorns that Baird didn't, Canfield wrote Baird a long description of the pronghorns he had observed in central California [12]. He explained that he had "some new facts that will sufficiently interest you to repay your for the trouble of learning them." He went on:

"I take the liberty of saying this because I have observed the Antelope for several years, have hunted them and killed a number of them (perhaps 150 of all ages and sexes), have caught and raised young ones, and am as familiar with them as most people are with goats and sheep."

What followed was a well written, scholarly but easily understandable account of the morphology, reproduction, habits and habitat of the pronghorn. He concluded:

"Much more could be added to the above, relative to the habits, &c., of the Prong-horned Antelope; but this must suffice; and if what I have written you will be of any value to science, you are at liberty to make such use of it as you think proper."

Interestingly, Baird did not "think proper" to use any of it, and Canfield's information did not come to the attention of the zoological community for another eight years. Apparently, the problem was that Baird could not accept Canfield's information that pronghorns shed their horns annually. J. D. Caton explained the issue:

"The first allusion which I find to the deciduous character of the horns of this antelope is in the letter-press of Audubon and Bachman ['Quadrupeds of America'], where they say, 'It was supposed by the hunters of Fort Union that the Prong-horned Antelope dropped its horns; but as no person had ever shot or killed one without these ornamental and useful appendages, we managed to prove the contrary to the men at the fort by knocking off the bony part of the horn and showing the hard spongy membrane beneath, well attached to the skull, and perfectly immovable.'

"The hunters were right, and the scientists were wrong... Some years later, on the 19th of April, 1858, Dr. C. A. Canfield, of Monterey, California, in a paper which he sent to Professor Baird of the Smithsonian Institute, communicated many new and interesting facts concerning the physiology and habits of this animal; and, among others, the surprising announcement that although it has a hollow horn, like the ox, yet this horn is cast off and renewed annually. This statement by Dr. Canfield was considered by Professor Baird so contradictory to all zoological laws, which had been considered well established by observed facts, that he did not venture to publish it, till the same fact was further attested by Mr. Bartlett, superintendent of the gardens of the Zoological Society of London, who, in 1855 [sic - 1865], repeated the fact in a paper published in the Proceedings of that society. In the February following, the paper which Dr. Canfield, eight years before, had furnished the Smithsonian Institute, containing the first well attested account of the interesting fact, was published in the Proceedings of that society.

"At the time I gave an account of Mr. Bartlett's observation, in a paper I read before the Ottawa Academy of Natural Sciences in 1868, and which was published by that society, I was not aware that the same fact had been previously communicated by Dr. Canfield to Professor Baird, else I should have taken pleasure in mentioning it" [13].

Although Baird chose not to publish Canfield's pronghorn observations, the letter may have been the catalyst to stir Canfield to a more active role in natural history pursuits, and also the impetus for the next fourteen years of interaction with the Smithsonian Institution. Within a year, Dr. Canfield had been recruited as one of ten Smithsonian weather observers in California (only four California stations had been established earlier) [14], a responsibility he maintained for ten of the next twelve years [15]. Local histories later identified him as "the Pacific coast agent and representative of the Smithsonian Institution" [16]. I find no record that such a formal position or relationship existed; I suspect he was merely a (volunteer) representative, not the representative. Nevertheless, his contributions were substantial, and duly recognized. He supplied over 100 specimens of birds and birds' eggs to the national collection, also a few mammals and invertebrates [17]. Through Dr. Baird, he was able to send specimens to other museums in Europe and the United States. Also, he acted as local guide and assistant to Smithsonian scientists working in the Monterey area. One such instance was cited by William. H. Dall:

"While acting as Chief of the Scientific Corps of the Western Union Telegraph Expedition, in 1865-6, I obtained leave of absence for three weeks, and proceeded to the town of Monterey, some ninety miles south of San Francisco, on the coast of California. This was in the month of January. During my stay, I devoted my entire time to the examination of the Mollusk fauna of that locality, which is very rich and varied. The results of much arduous labor (I was unable to dredge), in which I was most kindly seconded by Dr. C. A. Canfield, of Monterey, may be found summed up in the Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences [Volume III, p. 271, 1866] " [18].

Dall honored Canfield by naming Gibbula Canfieldi, one of the newly-discovered mollusks, after him: "One specimen of this modest little shell was found dead on the beach at Monterey. I take pleasure in dedicating it to Dr. C. A. Canfield of Monterey, who has done much for science with very slender means" [19]. A cursory search of the invertebrate literature yielded citations for seven other species named for Canfield, by Smithsonian scientists Dall and Richard Rathbun. (After Canfield's death, his personal collection of nearly 3,000 shells, was purchased by the State Normal School in San Jose [now San Jose State University] for $500 [20]; unfortunately, the "Canfield Collection" was destroyed in a fire at the school in 1880 [21].)

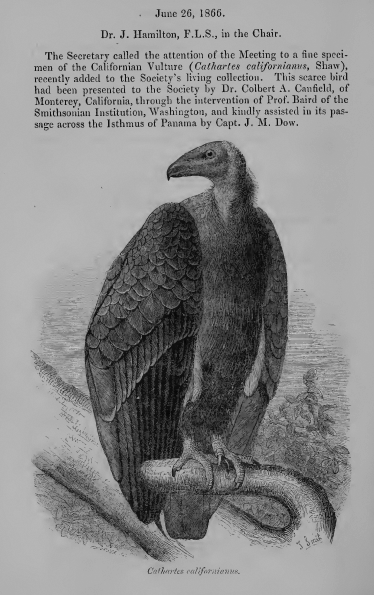

Figure 7. The first live California Condor outside the United States.

Through the 1860s, Colbert Canfield's name appeared regularly in the newspapers of central California. He provided detailed observations on the New Idria quicksilver mines, showing a good knowledge of mining practices [22]; wrote about the effects of current weather on crops and livestock [23]; and described the deleterious effects of wind-driven sand in the Salinas Valley [24]. He was quoted as knowledgeable on the ocean currents and temperatures of the Monterey Bay area, and on the iron springs existing on the coast [25]. His journal article on using the juice of the plant Grindelia robusta to relieve the symptoms of poison oak [26] was widely quoted, as was his information on the pronghorn antelope after it was presented to the Zoological Society of London [27] and the California Academy of Sciences [28] in 1866. His increasing scientific stature earned him the elected status of "corresponding member" of both the Zoological Society and California Academy [29, 30].

Dr. Canfield's involvement with California condors came fairly late in his career. Alexander Taylor cited him as having seen large numbers of condors in what is now San Benito County in the early 1850s [31], but the next record is from December 1864, when the local newspaper reported on the death of a condor:

"Some person, through accident or design, some few days since poisoned a pet vulture belonging to Dr. Canfield. The poison used was strychnine, and was probably administered in a piece of meat. The vulture was about eight months old, and measured across its wings, from tip to tip, 8 feet 9 1/2 inches" [32].

This condor may have been destined for the aviaries of the Zoological Society of London, and it wasn't long after the bird's death that Canfield procured a second live condor, a young bird taken from its nest in 1865. The bird was kept at Monterey through the winter of 1865-1866, then shipped to London by way of the Isthmus of Panama [33]. The Zoological Society of London received the condor in June 1866, the first live California condor ever in a public institution [34]. It lived in the Zoological Society aviaries two years, but died in late 1868 (cause unknown). The skeleton of that bird is preserved in the Natural History Museum (Tring, U. K.).

Spencer Baird and the Smithsonian had negotiated the Zoological Society condor acquisition [35]. In 1866, they arranged a specimen exchange with the Naturhistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria) that sent a Canfield-procured study skin to Europe [36]. They may have acted as intermediary in the transfer of another condor skin in 1866, from Canfield to the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago, Illinois) [37], and possibly a live condor from Canfield to the Royal Zoological Society aviaries in Dublin, Ireland in 1867 [38].

Dr. Canfield secured one condor egg for the Smithsonian in 1866 [39], and another condor skin in 1868. His final condor was another live bird, taken from its nest and raised at Canfield's home in Monterey. The local news carried a story about the bird in August 1871. "The Monterey Republican of the 10th inst., says: Chained to a post in Dr. Canfield's front yard may be seen one of those rare birds known as the 'California Vulture.' He was captured in the hills south of Carmel Valley. This specimen is some six months old, and is two-thirds grown, and is quite a formidable looking youngster. The doctor intends shipping him to the Zoological Society of London" [40].

A month later, there was a follow-up story: "Dr. Canfield's California vulture still stands guard in his front garden. The day after his arrival he nearly fell victim to the mischievous malevolence of the Monterey embryo 'Hoodlums,' who pelted him with a pitiless storm of small projectiles. Now he is respected as an old resident, and as he is likely to remain at his post for the next four months, it is consoling to be able to relate that juvenile curiosity respecting his vultureship has quite subsided, and hopes are entertained that he may reach the hands of Dr. Sclater, of the Zoological Society of London, who will so dispose of him that he may feast his eyes on princes, if he cannot feast himself on princes' eyes" [41].

That condor, apparently destined to replace the bird that died in London in 1868, was never shipped to England. Perhaps it died before it could be delivered, or perhaps Dr. Canfield himself became too ill to complete the transaction. The remains of what are probably that bird are in the U. S. National Museum.

In each of the eight cases in which Dr. Canfield had California condors in his possession - and with the 100 or so other specimens he contributed to the National Museum - he has been listed in the official records as the "collector." As it was common practice for agents, salesmen, and even museum preparators to list themselves as the actual procurer of specimens, it raises the question of how many of these birds Dr. Canfield actually killed or captured himself. He had a full-time career, not only as a physician, but also as the elected Monterey County coroner [42]. He served as his political party's secretary, was the city clerk of the Board of Registration and Election, and even found himself taking on such jobs as "directing and supervising the location of a road from this town to the Point Pinos Lighthouse Reservation." [43].

It seems likely that some of his songbird specimens were brought to him by others. (He noted in the above-cited letter to Spencer Baird that "while writing this last line, a boy comes bringing me a nest & eggs of some unknown bird, for which I give him a bit.") It also seems likely that - because of the time required to find condors, particularly nesting ones - Canfield hired hunters to procure some of his condors, or at least let it be known that he was looking for condor specimens. On the other hand, he was clearly an outdoor person who enjoyed close contact with wildlife. His statement that he had killed over 100 pronghorns and that he had raised young pronghorns [44], and the fact that he had kept condors in captivity for months at a time, suggest that he was fully capable of being the actual "collector." The truth is probably somewhere in the middle: that he obtained some of the condors himself, and procured some from other parties.

In 1870, at the age of 41, Colbert Austin Canfield's life must have seemed about as stressful as a life could get. He wrote a letter to Spencer Baird, apologizing for not sending some specimens that were expected from him. As noted above, he was supervising the locating of a road to the Point Pinos lighthouse (an unpaid favor to Colonel Williamson), he was making up the voting rolls for two upcoming elections, and was generally swamped with various political and governmental responsibilities. To this litany, he added (almost as an afterthought!) that his wife had just died in childbirth, leaving him with five children ranging in age from newborn to eleven years old, and he didn't know how he was going to afford domestic help to care for them. Still, he said, "I am constantly adding to my collections of Monterey species, but principally of shells, quite a number of new ones not yet named;--411 species in all. I am getting more birds' nests and eggs again." And: "As soon as I can 'get things in order again' I will try to forward to you all that I have collected" [45].

I haven't been able to determine if Dr. Canfield was able to "get things in order again." In late 1872 or early 1873, he died [46].

Chapter Notes

1. U. S. Federal census 6 July 1850: Chardon, Geauga County, Ohio.

2. The death notice for Colbert Canfield's mother, Lodemia (Benton) Canfield appeared in the Geauga Republic (Chardon, Ohio), 14 May 1850.

3. Colbert A. Canfield is shown as a student of "Dr. Hamilton" in the 1848, 1849 and 1850 catalogues for Western Reserve College (Hudson, Ohio).

4. Page 478 in: Anonymous. 1880. Pioneer and general history of Geauga County with sketches of some of the pioneers and prominent men. The Historical Society of Geauga County.

5. Pioneer and general history of Geauga County op. cit., pages 542-547.

6. I can find no definite date that Dr. Canfield settled at Monterey, but two records indicate 1855 as the most likely year.

Taylor, A. S. 1858. The southern California stage route. Sacramento (California) Daily Union, 23 January 1858: Taylor noted that Dr. Canfield had resided in Monterey County "for the last three years."

Canfield, C. A. 1866. Notes on Antilocapra Americana Ord. Paper read at the 5 February 1866 regular meeting of the California Academy of Sciences (San Francisco, California). "The following notes were taken from 1855 to 1858 in Monterey County..."

7. Pages 291-292 in: Anonymous. 1925. History of Monterey and Santa Cruz counties, California, cradle of California's history and romance. Volume II. Chicago, Illinois: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company.

8. Birth announcement, child of Dr. C. A. Canfield and Anita M. Watson, 5 February 1859. Sacramento (California) Bee, 3 March 1859.

9. Taylor 1858 op. cit.

10. Anonymous. 1858. Still a numerous family. San Francisco (California) Bulletin, 13 August 1858.

11. Page 666-670 in: Baird, S. F. 1857. Mammals. General report upon the zoology of the several Pacific railroad routes. Volume VII. Explorations and surveys for a railroad route from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Washington, D.C: War Department.

12. Canfield, C. A. 1866. On the habits of the Prongbuck (Antilocapra americana), and the periodical shedding of its horns. Proceedings of the Scientific Meetings of the Zoological Society of London [27 February 1866], pages 105-110.

13. Pages 25-26 in: Caton, J. D. 1877. The antelope and deer of America. Antilocapra and Cervidae of North America. New York, New York: Hurd and Houghton.

14. Commissioner of Patents. 1861. Results of meteorological observations made under the direction of the United States Patent Office and Smithsonian Institution, from the year 1854 to 1859, inclusive. Volume I. Washington, D. C.

15. Page 87 in: Anonymous. 1874. Annual report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, showing the operations, expenditures and conditions of the institution for the year 1873. Washington, D. C.

16. History of Monterey and Santa Cruz counties, op. cit.

17. U. S. National Museum of Natural History specimen databases.

18. Page 93 in: Dall, W. H. 1871. Descriptions of sixty new species of mollusks from the West Coast of North America and the North Pacific Ocean, with notes on others already described. American Journal of Conchology 7(2):93-160.

19. Dall op. cit., page 129.

20. Pages 53-54 in: Anonymous. 1889. Historical sketch of the State Normal School at San Jose, California. Sacramento: State Printing Office.

21. Historical sketch of the State Normal School, op. cit., pages 74-75.

22. Anonymous. 1860. The New Idria quicksilver mines. San Francisco (California) Bulletin, 25 April 1860.

23. Canfield, C. A. 1864. The weather, crops, stock, etc., in Monterey County. San Francisco (California) Bulletin, 26 May 1864.

24. Canfield, C. A. 1864. Drifting sands. San Francisco (California) Bulletin, 29 June 1864.

25. Pages 85-89 in: Anonymous. 1875. The hand book of Monterey and vicinity. A complete guide book for tourists, campers and visitors. Monterey, California: Walton and Curtis.

26. Canfield, C. A. 1860. The poison-oak and its antidote. American Journal of Pharmacy, Third Series, Volume 8(5: 412-415.

27. Canfield 1866 [Note 12], op. cit.

28. Canfield, C. A. 1866. Notes on Antilocapra Americana Ord. A paper presented at the 5 February 1866 regular meeting of the California Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 1866.

29. Page 5 in: Report of the Council of the Zoological Society of London, 29 April 1867. London: Taylor and Francis.

30. Proceedings of the California Academy of Natural Sciences (San Francisco, California), Regular meeting 19 February 1866.

31. Taylor, A. S. 1859. The great condor of California. Hutching's California Magazine 4(1):17-22.

32. Anonymous. 1864. A pretty pet! San Francisco (California) Bulletin, 21 December 1864 (quoting from the Monterey Gazette of 16 December 1864).

33. Renshaw, G. 1907. The Californian condor. The Zoologist (London), Fourth Series, 11(794):295-298.

Page 340 in: Baird, S. F., T. M. Brewer and R. Ridgway. 1874. A history of North American birds. Volume III, land birds. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown and Company.

34. Sclater, P. L. 1866. Living California vulture received in London. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 13:366.

Anonymous. 1867. Report of the Council of the Zoological Society of London, read at the annual general meeting, April 29, 1867. London: Taylor and Francis.

35. Renshaw 1907 op. cit.; also, the 29 April 1867 report of the Council of the Zoological Society.

36. Letter 27 April 1971 from G. Rokitansky (Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria) to S. R. Wilbur: "Specimen no. 40862... received in 1867 from Dr. C. A. Canfield, Smithsonian Institution, in exchange."

37. Specimen FMNH 95160 at the Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago, Illinois) does not have an identified source, but it was shot near Monterey in 1866, when only Colbert Canfield is known to have been collecting condors.

38. Sigwart, J. E., et al. 2004. Catalogue of raptors in the National Museum of Ireland. National Museum of Ireland database.

39. Some have given Colbert Canfield credit for collecting two California condor eggs, one in the collection of the U. S. National Museum, and one that was reportedly at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), but disappeared early. No official paperwork has ever been found concerning that egg, and Witmer Stone (Academy curator in the late 1800s and early 1900s) opined that there probably never had been a condor egg, but only a misidentified "foreign egg" (Letter from Stone to W. Lee Chambers, 4 April 1905; in the Chambers Collection, Bancroft Library, Berkeley, California).

40. Anonymous. 1871. A California vulture. Daily Evening Bulletin (San Francisco, California), 19 August 1871.

41. Anonymous. 1871. Matters in Carmel Valley. San Francisco (California) Bulletin, 9 September 1871.

42. Anonymous. 1867. Monterey County officers. Daily Alta California (San Francisco, California), 16 September 1867.

43. Letter of 20 May 1870 from Colbert A. Canfield to Spencer F. Baird: Smithsonian Institution Archives, Record Unit 7002, Box 17, Folder 2.

44. Canfield 1866 [Chapter Note 12], op. cit.

45. Canfield-Baird letter of 20 May 1870, op. cit.

46. I haven't found the date of Dr. Canfield's death, or his burial location. Only one reference so far found gives a relatively precise time.

Anonymous. 1873. Death of Dr. Canfield. Pacific Medical and Surgical Journal and Western Lancet 6(9):488.

"Colbert A. Canfield, M. D., died at his residence in Monterey, California, a few weeks ago. He was a man of considerable ability in his profession and a contributor, some years ago, to the columns of this Journal.”